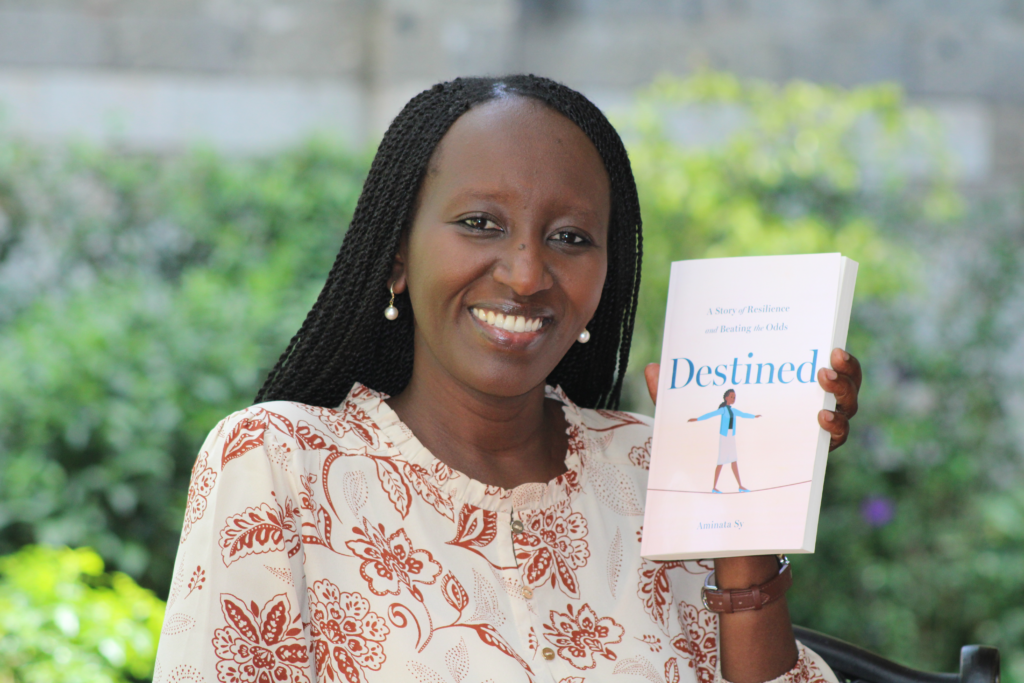

My memoir, Destined: A Story of Resilience and Beating the Odds, will launch on Tuesday, February 4, 2025! When the book appears on Amazon on February 4, I hope you’ll buy it for yourself and for a loved one.

Do you want to read a sample of Destined? Below I share chapter 3 titled “The Turning Point.” In it, I detail why and how I returned to school as a married mother juggling many responsibilities, earned my high school diploma equivalent, and went on to community college.

Chapter 3: “The Turning Point” from My Memoir Destined: A Story of Resilience a Beating the Odds

In January 2010, I started on a completely different path: I returned to school.

When Amadou and Aissata began attending prekindergarten in 2007, I often volunteered to help in their classrooms. I read to the children; participated in their activities, such as painting and drawing; helped serve them breakfast and lunch and cleaned up afterward; played jump rope with them during recess; and prepared them for nap time. Their classes held “100 book” challenges: parents signed up to read to their kids every day, and if the kids listened to 100 books by the end of the school year, they got a prize. I signed up for Amadou and Aissata, and we started reading nonstop, although I was less interested in the prize and more interested in the kids learning how to read well. I read to them about five books a day, at the library, at home during the day, and at bedtime. We went to our local library at least twice a week to check out and return books. Aissata started reading at three and Amadou at four! We ended up reading more than six hundred children’s books! I carried with me the experiences from my children’s prekindergarten classes long after we moved on, especially a rekindled desire to learn and a growing love of teaching. This experience lit in me a desire for knowledge that had been buried beneath life’s challenges since I had dropped out of school in Dakar. I went on to become an avid reader.

By the summer of 2009, I had become more confident reading in English and started borrowing memoirs and autobiographies from our local library. I wanted to learn more about the experiences of Black Americans—their perspectives, their struggles, their progress—and to see where I and my family fit within that picture. These are some of the stories that stayed with me.

I read The Souls of Black Folk, in which W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about “double consciousness,” the idea that Black people in America have evaluated themselves and their lives through the eyes and experiences of White people. Du Bois’s book was published in 1903; over a hundred years had elapsed since then, yet his point remained relevant.

I read I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou. Her life too was defined by racism and discrimination while growing up in the 1930s and ’40s in the segregated town of Stamps, Arkansas. I later read Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise,” which told the story of both the individual and collective abuse that Black Americans had experienced and their progress, as illustrated by Angelou’s own story of becoming a prominent writer.

I read The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., where he painted a detailed picture of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Hot tears dripped down my face as Dr. King described peaceful Black marchers in Birmingham, Alabama, fighting for the right to vote and be treated as human beings and American citizens, and how they were brutally attacked by White law enforcement with fire hoses, dogs, and clubs. Black people could not share anything with White people. Everywhere they went, there were signs that read “white only” or “colored only.” Dr. King refused to settle for these conditions. I also read A Call to Conscience, a collection of Dr. King’s speeches. Dr. King did everything he could to help Black people regain a sense of dignity and self-respect and had a tremendous impact on improving race relations in America. With every page, I gained a better understanding of racism in America and of the experiences of Black Americans both before and during the 1960s and down to the present day.

I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Malcolm Speaks, a collection of his speeches. Malcolm X’s authentic voice as he challenged an oppressive system that defined his life and that of his family stayed with me. He made a clear choice to either live as a free human being in America or die fighting for that freedom. He only went to school up to eighth grade but educated himself in prison and was able to change his life drastically. He was also willing to restart from scratch when necessary, as he did while imprisoned or when he lost his prominent position as a leader in the Nation of Islam after learning more about the Islamic religion through his pilgrimage to Mecca. At thirty-nine years old, in 1965, Malcolm X was murdered in front of his wife and children, fighting for human rights, dignity, freedom, and opportunity for every Black person in America.

I read Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama, the son of a Kenyan man and a White American woman. He struggled to find his place in America and to connect with his family in Kenya, and in 2005 he went on to serve as a U.S. senator, only the fifth Black American to do so. His story was that of yearning to belong and achieving against tremendous odds. I met Obama at a rally in our neighborhood in October 2008, when he was a presidential candidate and soon to be the first Black president of the United States. This was a time when the world seemed to revolve around Obama, yet shaking his hand allowed me to experience our shared humanity. If he accomplished extraordinary things, I felt, so could I and any other human being.

These stories and others provided me with a broad and intimate understanding of American society. Each story allowed me to contextualize systemic issues, such as poverty, racism, and inequities in education, employment, and housing, and also revealed the possibilities available to people, regardless of their personal background.

In our neighborhood in West Philadelphia and the shoe store where I worked, many Black Americans used to tell me, “You’re a beautiful Black woman.” I didn’t understand why they would always say “Black woman” instead of only “woman.” In Senegal, I was regarded, and regarded myself, simply as a girl, later as a woman, not a “Black girl,” a “Black woman.” I saw myself through the lens of my humanity, nationality, and ethnicity, not through race or Blackness. I hadn’t thought about what my skin color meant for my life.

The books I read and my own experiences living in predominantly Black-populated neighborhoods in West Philadelphia led me to understand that race, especially Blackness, defined people’s very existence and their livelihood in society, such as their education, health, job, housing, and safety. Getting this clearer picture of racism in America was critical in my integration into the country.

I had experienced poverty in Senegal and was experiencing it in America, so I wanted to break that cycle. Returning to school was one way I might lift myself and my family out of poverty. I knew that my kids would need my help with their education for years to come. I knew that I was in charge of helping them with their homework. I knew that my English was still insufficient to assist my kids long-term. I knew, too, that our family needed more than one consistent income to sustain us. Though my husband and I did our best to shield our children from our circumstances, our family survived below the poverty line. I wanted a different life for us, one that included enough financial freedom to live, not just survive.

For us, poverty meant a perpetual battle to live. My husband and I were always short on money to manage our day-to-day lives; we always worked in low-paying jobs and struggled to keep up with our bills and access healthcare. Our children didn’t attend quality schools and lacked safe places to play outdoors. We used government assistance to buy food and mostly shopped at thrift stores and flea markets for clothes, shoes, and household items, such as furniture and dishes. We lived in a low-income neighborhood, where our lives remained in constant danger of gun violence, and had to stomach ongoing police presence and witness continual clashes between police and residents. We were exposed to nonstop drug dealing, and alcohol was sold in every corner store.

In January 2010, I signed up for a General Education Development program, the GED being the equivalent of a high school diploma in the United States. At that point, Amadou was in first grade and Aissata in kindergarten, and my husband was still clocking in at his job as a parking attendant. He was fully supportive of my returning to school.

My morning classes took place at the School District of Philadelphia’s building on Broad Street; my classmates were all like me, adults. The teacher spoke fast and shared tips for taking the different GED tests for math, science, reading, writing, and social studies. She told us where to get books for our studies and how to sign up to take the different GED tests when we were ready. She also suggested simply taking the tests to gauge our levels of mastery, even if we didn’t pass. I took her advice, and within three months of completing the GED classes, I started signing up for the tests. I passed the tests for reading, writing, and social studies on the first try but failed science and math. Earning the GED diploma in the state of Pennsylvania required scoring at least 2,250 points total for all five subjects with a minimum score of 410 points per test.

At the GED testing center, I learned about a training program to become a certified nursing assistant in the state of Pennsylvania and thought that job could be a good way to support my family. I enrolled to train as a nurse’s aide while simultaneously continuing to take my GED classes. In the mornings, after I had dropped my children off at school, I attended the nurse’s aide classes. In the afternoon, my husband picked up the children from school; I returned home to help them with their homework and took them to their after-school activities, fixed dinner, and then went to my evening GED classes.

By the time I completed the nurse’s aide training, I had passed four out of the five GED tests but had failed the math test twice. I found a job at a nursing agency in downtown Philadelphia. The GED classes were also taught in the same building that housed the nursing agency, so I continued taking my math lessons there. Every week, I went to classes for two days and worked for three days. I retook my math test for the third time and passed! When I received my GED diploma in the mail, my husband framed it and hung it on our living room wall as a constant reminder of my academic progress. In June 2011, I attended two events celebrating two milestones: my graduation from my GED and nurse’s aide programs. My husband and children were there to cheer for me. Amadou shouted in both ceremonies as I walked across the stage to be congratulated, “That’s my mom!” The nurse’s aide program gave me an outstanding achievement award for earning my GED and nurse’s aide certificates at the same time.

The nursing agency placed me with different clients, all of whom were Black women in their seventies or older and suffered from critical health conditions. One of my clients lived by herself in a two-story apartment building. I helped her prepare her three daily meals and take a shower, and I cleaned up her place. Herself, her apartment, and her TV were all that she had.

I worked with another client who lived with her husband and was an amputee from complications related to diabetes. She had tried many different prosthetic legs that failed to accommodate her and finally received a promising one during my time with her. She sat in her wheelchair most of the day; I helped her wash herself, get dressed, put on her prosthetic leg, and practice walking with it. I tidied her bedroom, dusted and vacuumed her house, and prepared a breakfast of eggs, grits, sausage, and coffee for her and her husband. Their children were grown and had moved on with their lives, but one of them lived near their house and checked on them often. I liked working with that couple the most; they were welcoming and appreciated the services I provided to them two to three times a week. They still liked and respected one another after decades of marriage and contentedly entertained themselves with TV game shows like The Price Is Right and Let’s Make a Deal.

One week, I worked with a client twice and called the nursing agency to let them know that I was never returning to that house. That client lived with her son, newly released from prison, in an area of West Philadelphia that seemed abandoned because the majority of the homes there were either damaged or unoccupied. Her son wore an ankle monitor and reported to his probation officer daily. The house was crammed with books, stuffed animals, papers, dishes, clothes, shoes, and furniture. It looked like the client had just moved in and hadn’t yet organized anything. She was hooked up to an oxygen tank and sat on her couch watching TV, except when she used her electric wheelchair, attached to a lift, to ride upstairs, where I helped her shower and get dressed. The kitchen was filled with unorganized utensils, pots, and pans, but with difficulty, I managed to prepare some eggs and hot dogs and toast some bread. I felt suffocated and unsafe in that environment, both in the house and outside, and got intense headaches every day after I left.

Every week, I carried around emotional pain and stress connected to the many critically ill women I was helping. I couldn’t detach myself from the clients’ health struggles and isolating conditions. I couldn’t be a pleasant wife or mother in that unhealthy state. So when I stopped working to prepare for the birth of my third child, I never returned to the job. I learned that being a home health aide wasn’t for me, so I needed to try something else.

One night in March 2011, I learned that I had lost an important person in my life. Yaye’s grandson called to share that Yaye had gotten critically ill and was taken to a hospital but passed away soon after getting there. By that point, I hadn’t seen Yaye in almost ten years since I left Dakar and was preparing to visit her that July, but she left this world before I could accomplish that. Over the years, I had grown to truly appreciate Yaye’s contributions in my life, especially as I was raising my own children and I began to understand the responsibilities and sacrifices involved. I had maintained regular phone communication with her throughout the years.

The last time we spoke with each other was about two weeks before she passed away. Her death plunged me into profound sorrow, both because I would never see her again and because I had so narrowly missed an opportunity to see her once more before she died. During our last conversation, Yaye prayed for me and my family; she blessed us, leaving us in the hands of God to continue to guide and take care of us. I felt chills all over my body as she spoke; I sensed that she was telling me goodbye. My final words to her were, “Yaye, yen dji de djam,” meaning “Yaye, may we see each other in peace.” Yaye responded, “Yen dji de djam nenam,” meaning “May we see each other again in peace, my child.”

Today, Yaye continues to be in my heart and in my mind; she continues to guide me. I still miss her, but I’m comforted that we had prayed for one another, we had blessed one another, we had learned from one another. May Yaye’s beautiful heart continue to shine on earth through the blessing she poured into me.

Just as a critical person in my life died, a blessing was born. One late Thursday afternoon in January 2012, when I was full-term with my third pregnancy, I went to my routine checkup at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. The doctors checked me and the baby thoroughly and even ran blood tests and said everything looked fine, so I should go home soon. But a doctor came back shortly after to tell me that they saw a drop in the baby’s heartbeat, which meant they had to continue to monitor him and me longer than expected.

She returned later to tell me, “Based on the drop in the baby’s heartbeat, we can’t let you go home. We’re going to send you to the labor floor and start the delivery process.” I was in shock! I couldn’t believe what she was saying quite yet. So I asked her again, “Do you mean I’m going into labor?” She said yes and added that the baby looked pretty healthy, so they didn’t want to take any chances by sending me back home. “I just don’t know whether to cry or smile, because I’m not mentally ready yet,” I responded. “I understand; I’m going to give you some time to think about it,” the doctor said. By then, it was almost 11:00 p.m.

The following day, my husband had to be at work at 5:00 a.m., and the kids didn’t have school. I called my husband to share news of the planned delivery and told him to bring the kids to me early in the morning, so he could go to work. He brought the kids to me the next morning and headed to work. I was on the labor floor and under anesthesia but still felt pain from the contractions. My husband’s colleague replaced him at work, so he rushed back to the hospital at around 9:30 a.m., took the kids to stay with them, and returned with them to stick around until 5:00 p.m. when a doctor said I wasn’t yet ready for delivery. She would monitor my progress for two more hours and then decide whether to perform a cesarean section, which I very much wanted to avoid.

Thankfully, I ended up having a normal delivery. I called my husband to come back to the hospital with the kids, who were supervised by a nurse outside of the room where I was delivering my baby. I didn’t want my children to witness my agonizing pain or the delivery. My husband held my hand throughout the delivery as nurses and doctors surrounded me. At around close to 8:00 p.m., baby Ibra made his grand entrance into the world with beautiful cries! My husband, kids, and I were very happy to see and hold Ibra. I started breastfeeding him minutes after his birth and was discharged from the hospital two days later.

With the birth of my first child, I learned just how isolated and lonely my husband and I were and that people we thought we could count on would not be there for us because we were not worth their time and effort. With the birth of my second child, I learned to keep faith alive because no matter how bad the situation looks, things could always turn out for the better. With the birth of my third child, I felt whole and a sense of inner peace. I had gained confidence in myself as a parent, no longer grieved over our lack of external help, and made most decisions based on what I could personally handle and what my husband could support me in. My faith in God, myself, and the possibilities in life had grown over the years. I believed that my destiny was in no one else’s hands but God’s and that everything that was meant for me in my lifetime would happen.

I soon embarked on a journey totally unfamiliar to me; I decided to attend college. For years, my family and I were surviving paycheck to paycheck, squeezed by financial constraints, and I wanted that to change. I no longer wanted a mere job but a career that would sustain me and my family long-term and provide us with the financial freedom to live more fully and with less stress. I thought attending college could offer me more options to pursue a career. I also wanted to continue to improve my academic skills, so I could support my children in their ongoing education.

One day in the summer of 2012, I tied baby Ibra on my back and visited the same family friend who had previously babysat Amadou and Aissata. I told her about my plans to attend the Community College of Philadelphia (CCP) for the upcoming school year and asked if she could watch my baby boy when I started classes, and she agreed to do so. By then, Amadou was ten years old, Aissata nine, and Ibra five months.

I was a first-generation college student—that is the first in my family to attend college—and the only married woman I knew of in the Senegalese immigrant community in West Philadelphia who was attending college. The majority of Senegalese women in my community were hair braiders, and the majority of the Senegalese men were businessmen or worked as parking attendants or taxi drivers. I started my enrollment process at CCP having no clue about the time commitment or the academic and financial demands of college life.

My CCP enrollment process involved five steps. I completed an admission application, applied for federal financial aid, activated my student account, took a placement test, and finally registered for my reading and writing courses. To complete these processes, I had to go back and forth between two different CCP campuses with Ibra tied on my back or sitting in his stroller while I talked to financial and academic advisors and figured out federal financial aid. While I zigzagged from office to office, person to person, people often stopped me on the streets and campuses to greet Ibra and chat with him. “He’s so cute! How old is your baby? He is the cutest little thing!” Ibra would smile and flash his bright eyes at the people interacting with him. At times, I found quiet places on campus, covered Ibra in a blanket, breastfed him, and then walked to the next office for the next round of paperwork and decision-making.

The direction of my life began to change from this point on, though at first, I didn’t see what the new direction would be. My first concern was not selecting a major or a career but simply how I would get through the first weeks and semester of my studies. I knew that if I could complete the first semester of college, I could build on that momentum to continue. In the fall of 2012, I didn’t know what to expect, but I was eager to learn and knew that I especially needed to improve my English and math skills. I prioritized fulfilling my family responsibilities, remediating my academic weaknesses, and looking for financial aid.

I was taking a “leap of faith” on education and had no idea how it would turn out. I feared that I could once again fail as I had before. But there was a louder voice in my head that said that this time was different. I was going to school not just to get an education but also to better help my kids with their studies and further their intellectual growth. I was going to school because my family and I needed a better financial situation. I had a much deeper desire to learn than my teenage self had had. This time, my education could make a difference in my life and that of my family.

Ms. Shashaty was my first college professor. She combined expertise, seriousness, and clarity in her teaching. I took two remedial English courses with her, one focused on reading comprehension and one on writing and grammar. I told her toward the beginning of the semester to bear with me throughout the course because I was learning English and still needed a lot of practice to improve my writing skills. Most days that semester, I attended classes with excruciating pain in my chest from not breastfeeding Ibra during the long hours I was in school. My entire chest felt like someone was poking needles into it. I didn’t tell Ms. Shashaty or other classmates but simply did my best to get through each class, hoping that eventually the pain would stop.

I had another serious academic weakness. I couldn’t type on a word processor and didn’t know how to learn to do so. When Ms. Shashaty first assigned us an essay to write, I worried that it could be the end of my college career. I asked an academic advisor if CCP offered any typing classes because I didn’t know how to type and many of the assignments required typed papers. The adviser said that the college didn’t offer a typing class, but many students struggled with a similar problem and were able to get through their classes. Her answer didn’t provide a solution to my problem, but at least I knew I wasn’t alone and could maybe get through my classes without knowing how to type.

I first handwrote my papers in notebooks, had them checked by English tutors, and edited them. Then, I would spend all day at the college’s computer lab typing them, then hours editing them with different tutors, and then more hours back at a computer incorporating those edits. My eyes watered with tears of disappointment and frustration when I first typed an essay because of how excruciatingly slow I was. I wondered, How could I get through college at this rate? But I persisted anyway. I sat in the front of every class to minimize distractions, took notes, participated in discussions, asked the professor questions, and completed all my assignments on time.

Outside of class, I squeezed learning into my life’s routine. Before class, I dropped Amadou and Aissata off at school, prepared Ibra and his diaper bag with all his needs, took him to the babysitter at around 11:15 a.m., and then went to CCP for my classes. My husband picked up Amadou and Aissata from school, made sure they ate lunch, and stayed with them until I got home. After I left CCP, I picked up Ibra from the babysitter, breastfed him, helped his siblings with homework, took them to their after-school activities and brought them back, fixed dinner for the family, and then stayed up until midnight or later completing my assignments. I did my schoolwork while breastfeeding Ibra, while carrying him on my back, or while he was asleep. I took all of my class materials with me to the after-school activities of Amadou and Aissata and did my work while the kids swam, played basketball, or practiced karate at our local YMCA. I was always on the clock, doing something related to family or school; I only had time to myself when I went to bed.

I learned how to read texts critically and to annotate, summarize, paraphrase, and respond to them. One skill that I really enjoyed learning from Ms. Shashaty was annotating a text, and I applied the method to all of my readings because it allowed me to get intimate with written words and their writers and to gain a deep understanding of the materials I read. While reading texts, I used a pencil to underline the most important sentences in each paragraph and drew star symbols next to them to show their importance. I summarized each paragraph or page I read in one or two sentences in the margins of the texts. I circled words I didn’t understand and looked them up in a dictionary. I also circled the names of people who were featured in the text to keep track of the information given about each one. In a separate notebook, I compiled vocabulary words that I would later look up and write sentences for. I reacted to the texts as I read by drawing smiley faces or sad faces to show how I felt about the information. I wrote a question mark next to passages I didn’t understand and an exclamation point near something exciting or dramatic. I asked questions on the margins, almost as if I were talking to someone, maybe the author. I wrote “agree” or “disagree” next to a paragraph or sentence I felt strongly about and connected my readings to my personal experiences. I read aloud to myself for about ten minutes every day to practice pronouncing words and sentences. I listened to the words I struggled with, using an online dictionary and rereading them aloud over and over until I got comfortable saying them. By the time I needed to summarize, paraphrase, or respond to the texts, I was prepared for such assignments. I also worked continually with English tutors to help me edit my papers.

Ms. Vicky was one of those English tutors who poured so much of their time and knowledge into me. She edited, corrected, and explained the errors in my grammar, spelling, punctuation, sentence structure, and word choice. The combination of Ms. Vicky’s one-on-one, patient English tutoring style and the ongoing questions I asked her to better understand her edits and avoid repeating them for the next paper allowed me to improve my writing skills with each session. I thought that I was making only slow progress, but looking back I see that, given the many writing skills that I needed to improve on, my learning process was relatively fast, and that was because of the support I got from Ms. Vicky and other English tutors as well as my own commitment to improve.

I went to the Learning Lab for tutoring at least ten hours a week throughout that semester, and outside of school, I spent another ten to thirty hours a week practicing my writing and reading skills in some capacity, whether it was looking up words and writing down their meanings, taking online grammar quizzes, annotating texts, or reading aloud to my children. Learning academic English became part of my daily routine. I was so grateful to Ms. Vicky that I wrote her a thank-you note for her efforts in supporting my learning. My English learning experiences that first semester opened my eyes to my potential as a student and trained me to become better at juggling marriage, motherhood, and education.

At the end of the semester, I met with Ms. Shashaty for her overall feedback about my learning progress and to get my final grades for her two courses. In one class, I finished with 94 out of 100, and in another class with 96 out of 100. Since these courses were pass/fail, my scores would not show up in my academic record, but Ms. Shashaty told me that students in remedial classes generally didn’t score as high as I had and added, “Aminata, you have what it takes to get your master’s degree.” I was so puzzled by her statement that I wrote it down to reflect on. I remember thinking, “How do I have what it takes to get a master’s degree? I’m an English learner, just wrapping up remedial classes I had to take because my English skills were not adequate for college-level work.” But just as a part of me questioned her assessment of my academic abilities, another part of me believed her. Ms. Shashaty knew her subject matter well and had also gotten to know me as a student. I handed Ms. Shashaty a thank-you note and told her how much I appreciated learning from her. I kept her words about the master’s degree somewhere in my mind, but it seemed unattainable to me. Instead, I focused only on signing up for classes for the following semester, while still worrying about how to balance my home and school lives.

That day, I went home and talked to my baby, Ibra, who was ten months old, as I wept tears of joy. “Thank you, my baby, for letting me learn. Thank you for being a good baby to your mommy. I finished my first semester with good grades! May God bless you and always protect you! I love you, baby!” I gave Ibra so many kisses and hugs for helping me in my college education by accepting the babysitter and bottle-feeding; if he hadn’t, I would have dropped my studies. Throughout my time in school that semester, I felt Ibra’s absence and wanted to be with him. The piercing pain in my chest for not breastfeeding him remained a constant reminder that I was away from my baby for many hours. But I suppressed those feelings so I could focus on my learning and then gave Ibra my full attention when I returned home.

Ibra had cried and thrown tantrums for about two weeks, and then he started to embrace his new routine of being away from me for hours at a time and of being bottle-fed with baby formula. Those were big changes for him and for me, and we didn’t know how they would impact us or if we could sustain them for months. Without having a clue as to what was happening, Ibra helped me start and continue my college education. Ibra loved to stay with me and to breastfeed as much as he wanted, cuddle up in my arms or be tied on my back, sit leaning back against my chest while I read aloud to him story after story, or stroll around through our West Philadelphia neighborhood on our way to our local library or the YMCA.

The following semester, in the spring of 2013, I enrolled in two college-level English classes and a remedial math course. My English professor was Ms. Ravyn, a dynamic and passionate woman who taught with confidence and conviction. In her classes, I dove deeper into reading literature and writing essays. I liked hearing Ms. Ravyn read aloud from our different texts and how she had students, including me, also read to the class. I liked her passion for teaching; I felt her love for literature and her desire to see her students perform well in her classes. I went to her office hours almost every week to ask questions about assignments and to have her critique my papers as I was in the process of writing them. She gave clear feedback and edits that allowed me to improve my essays week after week.

Her paper assignments covered a range of social issues in the United States, such as inequities in education from kindergarten through college, immigrant experiences in the K–12 grades, racism, classism, toxic masculinity, and media depiction of women. Thinking and writing about these social issues increased my desire to engage and be a part of the solution, especially when it came to education. I grew to enjoy the process of coming up with an idea for an essay, writing about it, getting feedback and editing support to improve it, and finalizing my work for submission. I became appreciative of the writing process that I had dreaded in my two previous English classes because I started to see how it helped to clarify my thoughts and even shape my actions. I became faster at editing and typing my papers. Ms. Ravyn would later write a scholarship recommendation letter on my behalf that brought me to tears of appreciation for the growth that I experienced in her classes and how she recognized that growth. Below is an excerpt of the letter.

“When I claim that Aminata stood out from her peers on the first day of class, I am not saying so lightly. I was pleasantly surprised by her level of commitment and alert attitude during our first three-hour session. Her energy and sharpness simply did not flag. In the subsequent months as I was getting to know her, I never witnessed a moment when she wasn’t energetic, focused, and positive. I am describing these aspects of her personality to impress upon you what I think makes Aminata such a success no matter what she attempts—she knows how to learn, and she exemplifies how resilience and persistence yield great results. If you couple her personality with her organizational skills and her work ethic, you will see a portrait of a student who will be able to do great things in all manner of rigorous academics.”

Ms. Ravyn’s letter reminded me of the many hours that I had spent thinking and working through different essay topics, meeting with her and tutors for support, and editing at least ten drafts for each assignment. I discovered in her class that I loved writing and wanted to continue to improve. Her class papers became less about completing those final drafts and getting good grades and more about the actual writing process and the intellectual exploration of social issues that millions across the United States, including myself, dealt with. That’s why I set a personal standard of excellence for the papers because I genuinely cared about the issues that I wrote about and wanted to discuss them as clearly as possible. I was beginning to realize that I loved learning languages for their own sake. As a child, I had to learn several different languages to communicate with the important people in my life—Pulaar, Wolof, French—so learning a fourth language, English, did not seem like an impossible undertaking. In addition, I took three consecutive Spanish courses at CCP and as a tutor, passed on what I knew about the language to my peers.

Throughout my academic career, I met professors, instructors, tutors, advisors, administrators, and students who were willing to support me in my efforts to improve and get to the next level. I believe that once you take full ownership of your academic career, you’ll attract people who can guide you in achieving, even surpassing, your goals. Pursuing anything worthwhile can feel and be lonely; however, if you open your mind and heart to getting support, people will help you improve beyond your expectations.

In the spring of 2013, I also took my first math class at CCP, with Mr. Reading, an energetic professor. During our first day of class, he asked students to introduce themselves to the class. When it was my turn to speak, I said that I had never liked math and struggled with it throughout my schooling and ended with “I’m ready to learn, and I’m happy to be here.” Mr. Reading listened and smiled, told me that I was in the right place, and welcomed me to the class. That was the lowest-level remedial math class that the college offered; it taught arithmetic—adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing—and was designed for students like me, who were relearning the basics. The class had its special book from which Mr. Reading assigned homework after every session. When he assigned us twenty problems, I did forty of them or even more, until I felt confident with the concepts. I was relearning arithmetic, because I had been out of school for over a decade, and I had forgotten how to do it.

I decided that memorizing the times table would help me solve many of the math problems. Every day, I committed to writing the times table from two to twelve in a composition book. I scored in the nineties for the first two math assignments and 100 in the third one! That day, I called my husband over our class break to share the news of my grade, and Mr. Reading’s reaction to it. I told my husband that I couldn’t believe that I scored a hundred in math, given all of my shortcomings with the subject and that Mr. Reading took about fifteen minutes of class time praising my work. He began by saying that he didn’t mention individual students’ grades in his classes but had to speak up on mine. He became teary-eyed with pride as he reminded me that I had admitted my weakness in math but had constantly put in the work and had improved in a relatively short amount of time. He added, “You are the reason I teach. Students like you are the reason I teach.” I felt both honored and put on the spot. I simply wanted to improve my learning; I didn’t want to be highlighted for doing so. Many students congratulated me during our break. The hours of practicing math and doing the homework paid off, and I continued to maintain high scores in Mr. Reading’s class until I completed the course—me, the woman who didn’t know her times tables a few months earlier! If you don’t give up, anything is possible.

I knew from that class that math would no longer be a barrier to my education, though it would continue to be a challenge. I had memorized my times tables and could add, subtract, multiply, and divide with confidence. I asked the professor and tutors clarifying questions regarding specific math problems that I struggled with, practiced problems until I felt confident I understood them well, and sought out tutoring support throughout the semester. I knew that I had found a learning system for math that worked and that I could apply it in the upcoming higher-level courses on the subject. As in my other classes, I gained more confidence in dealing with academic challenges and overcoming them through practice and a genuine interest in learning and improving my skills.

My academic progress at community college paid off in other ways as well. I went on to win a scholarship that covered my tuition, books, and fees throughout the remainder of my time at the school, and I was selected for a few more scholarships connected to my academic achievement. I felt a great sense of relief that I could learn without constantly worrying about how I would pay for my education. With my husband’s encouragement, I also decided to major in international studies after completing my first year at the school with the intention of hopefully pursuing a career in U.S. diplomacy one day.

It was in the spring of 2014 when I took a class at CCP that made my entire body tremble and my mind race: public speaking. I had the choice of taking a creative writing course or public speaking. I decided to take public speaking because that’s the class that terrified me, and I wanted to overcome that fear. In the Senegalese culture in which I grew up, looking directly into people’s eyes, especially adults, was considered a sign of disrespect. In American culture, looking away or looking down when talking to people is a sign of not being trustworthy and confident. I wanted to get comfortable speaking in front of people while making eye contact with them as much as possible.

In that course, I wrote and delivered six speeches based on my own experience, research, and the principles of effective public speaking that we learned in class. Students, about twenty of us, were graded in real time as we delivered our speeches; we got written feedback from our peers and the instructor, focusing on content as well as vocal and nonverbal deliveries. During our first session, the professor said, “In this class, you will sink or swim.”

My speeches covered key life lessons from Marian Wright Edelman, an activist for civil rights and children’s rights; celebrated my aunt Yaye; shared an aspect of Senegalese culture by demonstrating how women tied babies on their backs; addressed racism and race relations in America; and proposed recommendations for the African continent and its youth. As I delivered my speeches, I decided to swim and not sink, though my hands and voice trembled, my body rocked back and forth, and my eyes barely saw the audience. Many peers pointed out that I looked down often and that at times I spoke too fast. But overall, the students wrote that my delivery was clear and memorable and the content purposeful and inspiring.

With every speech, I became a little less nervous, looked at the audience a little more, and read my notes a little less, but delivering the speeches never felt easy, even with all of my preparations. My peers and professor had a different perspective than I did; they focused on the progress that I had been making over time, especially in my level of confidence.

Our fourth assignment involved selecting a speech by someone else and delivering that to the class within a time limit. I chose a commencement address by Marian Wright Edelman, delivered at Lewis & Clark College on May 10, 2014, in which she talked about ten life lessons. I selected six of them: (1) to know that nothing is free, (2) to assign yourself something to do, (3) to never work just for money, (4) to not be afraid to take risks or be criticized, (5) to listen to yourself, and (6) to never give up. After I delivered that speech, one student wrote for his feedback, “I don’t think I’ve ever said this about anyone before, but you’re going places. Run for president; I would vote for you.” Another student wrote, “You really made this speech yours. For a minute, I thought you were that speaker.” I maintained an A grade throughout that course, scoring from ninety to ninety-nine for my various speeches. More than anything, I was proud of challenging myself to speak to an audience despite my fears and to do my best to learn and to share with peers an authentic part of who I was. Sometimes, our best learning experiences come from situations that scare us, but when we embrace them, we meet a more confident version of ourselves on the other side.

Our final speech assignment was to project ourselves into the future and see ourselves as professionals delivering a message to a relevant audience. I spoke as the U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs, delivering a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on improving the economic conditions of Africa, especially of its children. I imagined that all of my classmates were heads of state and that the professor was the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

My speech connected my story to that of other African girls and focused on Senegal. I talked about the need to educate children, especially girls. I proposed three recommendations for the African continent: to invest in the education of African children, to protect and preserve the continent’s natural resources, and to address climate change and pollution leading to droughts and food insecurity. The professor wrote for his feedback, “I love the humanitarian purpose of your speech and your excellent knowledge of the topic. It was a wonderful capstone to the semester.” A student shared, “I really enjoyed your speeches all semester long. They were very beneficial to us or other audiences you are referring to.”

I had willingly signed up for a course that terrified me, one in which I could have truly embarrassed myself publicly because there was nowhere to hide. Up to that point, I had never delivered a speech to any group of people, large or small, and didn’t know how the semester would go. Still, I approached the public-speaking course as I had approached the others, by counting on careful preparation to make up for whatever deficits I might have, as well as for my anxiety. I asked the professor questions inside and outside of class in order to better understand his expectations; I wrote, rewrote, and edited my speeches and practiced them in front of tutors, my daughter, and the mirror. By the time I stood in front of the class to speak, I had reduced my anxiety by half. I still trembled and still doubted myself, but I was also confident that I could lean on my preparation even if I forgot my speech. The public speaking class solidified my level of confidence in what I could accomplish once I decided to go for something. In many ways, my fear of speaking in front of people was more about a mental barrier that I needed to push through; it had nothing to do with whether I was capable of delivering speeches. This was true for the bigger challenges in my life as well. I came to accept that how far I could reach depended on my beliefs about myself, even if all odds were against me.

In March of 2015, I experienced another major milestone, an acceptance letter from the University of Pennsylvania! “On behalf of the Admission Committee, it is my pleasure to offer you admission to the Bachelor of Arts in LPS at the College of Professional and Liberal Studies for Fall 2015. Your commitment to personal excellence makes you stand out as someone who will thrive at Penn and make a solid contribution to our community. We believe that you and Penn are very well matched for each other.”

CCP wanted to recognize and highlight this achievement to encourage other students, so its communications team organized a photo shoot and an interview with two local publications: PhillyVoice and the Philadelphia Inquirer. Their reporters interviewed me along with three other CCP students who were also transferring to Penn in the fall of 2015. I told reporters about my plans to study international relations at Penn and my hopes to work in U.S. diplomacy and to contribute to improving education and youth employment in Senegal. I said, “What I took away from this experience is that my voice matters, that I can accomplish anything I want to…I’m not afraid of anything anymore.”

I echoed those thoughts in an article published in CCP’s student newspaper, the Vanguard, on November 26, 2014, titled “Thank you CCP.” In the piece, I thanked professors, advisors, tutors, scholarship staff, the Vanguard team, and my husband and children, all of whom helped during my time at the college. I talked about the many academic and personal struggles that I dealt with and my dramatic improvement. I wrote, “Today, I am a totally different student. I am confident and believe that I can achieve any level of academic success when I put my mind to it. CCP has shown me that my potentials are limitless as long as I am not afraid to tap into them.”

I’m telling you of these achievements to show you what you are capable of if you focus and work hard. What I accomplished, you can too. I started out by learning many basics in academic English, such as grammar, vocabulary, punctuation, and pronunciation, and persisted with the process consistently, which eventually led to concrete progress. Whatever you put your mind to, you can achieve.

I don’t mean to imply that hard work and belief in oneself are all that one needs to achieve their goals. One must also be willing to make sacrifices. Returning to school, especially as an adult with different responsibilities, could cost you more than you imagine. That’s why so many people quit. You have to be willing to commit yourself to being a student and give up activities that interfere with that commitment.

I took full ownership of my learning by making it a top priority in my life. This meant any activity I engaged in at the time revolved around my marriage, children, or school. I cut out social activities, such as attending the childbirth or marriage ceremonies that took place frequently in my immigrant community. I stopped watching TV, only occasionally paying attention to the news; I didn’t use social media. I picked up phone calls from family members in Senegal only during the weekends. I focused on my education by weaving it into my day-to-day life, such as studying while waiting for my children during their after-school activities. Given the many academic weaknesses I needed to work on while juggling family responsibilities, I still doubted if I could make the necessary progress in my education. But I didn’t have the choice of relinquishing any of my responsibilities; my only choice was to figure out how to fit education into my life as it was.

Many people I knew, both close and far away, misunderstood me; many distanced themselves from me because they couldn’t grasp what I was trying to achieve. So part of what I had signed up for when I returned to school was being misunderstood, isolated, and lonely while navigating experiences that were completely new to me. What I did in returning to school was just try. I tried without knowing what I was doing. I tried with some support and learned along the way. I tried with zero guarantee that I would finish the first semester, let alone graduate. I tried in confusion, frustration, tears, fatigue, and isolation. Just try and see what happens.

I failed many times in school growing up, not because I was incapable of learning but because I lacked the necessary support system. Those failures, my separation from my parents, and my childhood trauma bruised my self-esteem and belief in my capabilities. What I learned, though, is that we must distinguish between what happens to us in our lives and what we choose to do with our experiences. Those are two different things. We always have the choice and power to define what our life experiences mean to us. I chose to give school another shot, and it worked. I hope you’ll always choose to bet on yourself even if all the odds are against you. What meaning do you want to give to your most difficult life experiences? You have control over your mind and attitude; use them to unlock a sea of possibilities.

Graduation day marked the end of one academic experience and the beginning of another. On the morning of May 2, 2015, I graduated with the highest honors among more than 2,000 CCP students and was only one of three people to earn an associate’s degree in international studies. My family and I shared the joyous occasion; I felt so much gratitude for both the struggle and the progress.

Thank you for reading. Wishing you all the best.

Keep going!

Order your copy of Destined and download this FREE chapter here: aminatasy.com/book

Hi, I’m Aminata Sy. I’m the author of the memoir Destined: A Story of Resilience and Beating the Odds, in which I write about how I started out in America as a high-school dropout and non-English-speaking immigrant and yet went on to earn a high-school equivalency diploma and associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees and to land a dream career. All that time, I was a wife and mother too and had plenty of family responsibilities. I help community college and university students excel in their education, so they can transform their lives for the better. Subscribe to my newsletter here: aminatasy.com/join-newsletter.

Are you ready to transform your life through learning?

Join our newsletter to receive monthly exclusive insights and wisdom from Aminata Sy, whose incredible journey of self-transformation has moved and inspired thousands. Aminata offers tips to community college and first-generation Ivy League students on learning, writing, reading, and resilience. You can unsubscribe at any time.